A conversation with Alex Isembard

The start of a conversation

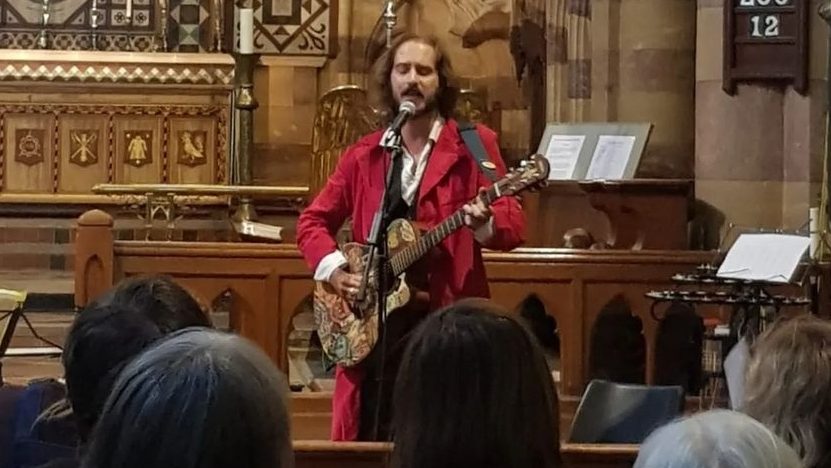

Alexander Isembard is a poet who captures his thoughts and observations by putting them into poetic folk songs, using his pseudoname Isembard’s Wheel. Let me put empahsis on the word poet, because once you’re done reading this blog, you will have learned a whole lot about poetry from him.

What started as a casual exchange of thoughts about music between him and myself, ended up in a small poetic discourse on the topic of transferring meaning through the arts, specifically poetry and song. It was refreshing and inspiring to talk to him about this subject and therefor I would like to share the highlights of this conversation with you.

When admitting to admiring Alex’ songwriting skills and his way with figurative language and metaphors, confessing I often end up with literal texts myself, Alex had this to say:

“We draw on the poets of our cultures. Passion leads -always- and from there onwards it is really a matter of recognising language first and foremost as a precision tool.”

Alex says that being a songwriter is to be constantly haunted by ghosts. Always tapping you on the shoulder, “have you finished, yet? Have you made me my body?” and we do, with the clay of language, make vessels for the ghosts. If we rush, then we might make the wings wrong or the eyes out of place and the poor, damn thing will follow always at our heels because it isn’t made correctly. But when we take the time to fashion it rightly, we can let the ghost go in its new body of words. We can always enjoy the sight of it flying with its kin, as anyone listening to its song may, but importantly it will never haunt us again.

Alex believes this is an experience we all can recognise however we articulate it. He confesses he has only ever written two songs which he rushed and they did indeed follow him around as broken homunculi for so, so long.

Into the philosophical and poetical

Once we started talking like this, he got me hooked. From the shape of unfinished songs, we moved to the shape of finished songs and in particular the language they’re written in. It’s an exceptionally fascinating concept, especially for us artists. I find myself drawn to my native language as it makes me feel like I can bring across the true meaning of the song more clearly and sincerely. At the same time, I’ve made this music business my only job and have to keep an eye on finances, meaning I’ve got to take my fanbase into account. I didn’t start making art for the sake of money, but now that I’m making money with my art, I find myself entangled in dilemmas and thoughts regarding my authenticity, skill, and quality as an artist.

As humans we can’t help but look around. “What are they doing?” “How are they doing it?” and comparisons are far too quickly made. Hearing other artists and feeling the meaning of their words in my heart makes me wonder whether I’ve got that essential quality myself, especially across languages. My hero Luke Kelly is a shining example of sincerity and ability of captivating an audience, even across languages and television screens, with a big chunk of his audience having a different first language than English.

“I think the best we can do is just create however we create, on a song by song basis.”

On this topic, Alex says that he often makes this comparison between languages, because he has had a few different languages in his upbringing himself and enjoys the poems and songs from all those cultures. Though he wonders: “Have I really truly heard those songs or poems?” Alex grew up bilingual Spanish and studied Russian at university, reading Eugene Onegin in both English and in Russian, finding it was markedly different because certain idioms don’t exist in English, metaphors don’t have direct equivalents, and (worst of all) there’s no way to preserve meaning AND the rhyme. Even though he understand the words, he confesses not having the cultural basis for a lot of the turns of phrase, so he wonders whether he really “understands” the songs.

“I get the words, sure, but where do you draw the line? Capturing meaning across languages is such a balancing act.”

The funny thing is, Alex says, the amount of idiomatic phrasing that goes into a lot of poetry or poetic songwriting likely makes it all the more difficult to translate. One can capture the translation, or the meaning, or the intent, but rarely all three. Which kind of also gives it that extra value that makes poetry special. Conveying meaning beyond the literal meaning of the words themselves. A 1+1=3 kind of thing, without which we could easier translate, but that would go at the cost of that magic mix that comprises poetry. It’s the spoken word reshaping reality from the perspective of the listener, yet it’s fascinating to think about how different listeners (even within the same audience, let alone cross-cultural ones) derive different meanings from the same words.

The meaning of poetry

Especially during times of mourning (funeral letters most profoundly) people who never had any interest in poetry at all still add a piece of poetry or a small rhyme which in itself speaks of so much more and reaches so much deeper than would a thesis about why the person will be missed. Alex agrees, saying this is one of those strange quirks of human nature, fascinating in themselves. His favourite is the one for the poet John Keats, “Here is one whose name was written in water” Beautiful.

And then there are artists who can capture an entire audience into the same dreamy state, binding them all together, regardless of politics, religion, culture. Songs where everyone somehow agrees on what they should mean and everyone feels that same meaning resonating within them. That’s the other side of the spectrum where there’s unity in understanding, as opposed to deriving meaning from one’s own perspective. Both being incredibly powerful and essential for the art to be just that; art.

“Meaning can transcend the literal and even the metaphorical.“

Alex has this to say about that: “I could write you a song about the time I went surfing and you might get it or you might not (depending on your life experience) but if I wrote a song about how I feel when I am surfing then you’ll get it if I do a good job, because you can relate it to something in your own life that feels like how I do when I’m surfing.”

The meaning of songs

When the topic of old songs and old unused lyrics comes up, Alex tells me he never minds holding onto a lyric that feels right but doesn’t fit or work somehow. “Often, I just haven’t lived that moment yet.” I find myself agreeing with him and the mysterious ways of songs. I’ve written songs which didn’t make much sense, until suddenly they fit perfectly to an event that happened months or years after the writing!

“It’s easy to get quite spiritual about poetry/songwriting.”

When asked how he goes about writing his songs, Alex says that it’s about being attuned to a state of constant awareness, yet seen through a romantic lense. You don’t want to miss a moment, if you can help it, so you write it down or record it in a different way. Even if you don’t use the lyric or image now, you will preserve it and that contributes to the archive of yourself that lends poetry depth over the course of a lifetime. There is an element of mysticism in Alex’ attitude to songwriting, which he thinks might be linked to the influence of the bushido attitude to perfection in practice on his life.

Finishing up, we talked a bit about specific songs. Or at least; I once again couldn’t help myself but to remind him that The Cliffs is my absolute favorite and I can’t wait to play his upcoming album “Long Run the Fox, Long Fly the Lark” on loop. He had this to say bout the album: It’s a relief to have it existing outside my head for the first time in years.

“I’m letting my ghosts go. I can watch them fly and sing but they’ll never weigh down my shoulder again.”

His album will release live at The Gate in Roath, Cardiff. Saturday the 7th of October [Tickets]. After that, we can all listen to the album through various media and buy it to support Alex himself.

A light note

When the conversations slowly turned towards my own songs, Alex confessed the truth: I’ve been using your stuff at our weekly Dungeons & Dragons sessions. For real! Every Tuesday I’ve murdered characters and monsters alike to your tunes.

“All fall beneath my fell blade, eventually.”

Thank you, Alex, for having this interesting conversation with me. I wish you all the best during your release, during your D&D sessions, and of course in the rest of your musical poetic life! To my friends and fans reading this and having arrived all the way to the very end of this blog; give Isembard’s Wheel a few spins on Spotify!